Back to Gary Numan index

Previous

WHAT IS A MACHMAN? (10)

(10) Interestingly - at least for us old hippies - Numan says (Goodwin: Tracks) that the word comes from a short story he read in Oz magazine. Machine men is an obvious inference but there's also 'macho men', or would be if Village People hadn't managed to render that concept on the gay scene so completely ludicrous.

The following song - 'The Machman' - would also be, following the sci fi scenario, about an electric android:

'I saw him turn on

Like a machine in the park

Saying 'please come with me'

But you've been there before

I saw him whirr away

Into the night

Like a nightmare on wheels

Saying 'never again''

Sutton interprets this as about 'a close encounter with a killing machine that could have taken his life but which lets him off with a warning, perhaps because of his youth.' I interpret it more simply as the singer being propositioned in 'the park', these encounters being, as so often they are, polite - 'Please come with me.' 'Please sit down' (Are 'friends' electric?), 'Won't you visit me please?' (Cars), 'A vague feeling of panic/as a man leaves, saying Thank you.' (It must have been years).

It isn't clear if the man has been successful in his proposition. I suspect he has but is immediately overcome by a sense of guilt, saying 'never again'. But we've been here before and we know he'll be back. As will the first person protagonist. And we know this sort of activity gets us into trouble with the police and can lead to public disgrace and attempts at medical treatment:

'Yellowed newspapers

Tell the story of someone

"Do you know this man?"

Tomorrow the cure

Only the police

See night time for real.'

A very strange last line that. Does it indicate the difference between these sexual encounters as experienced by those taking part and what they must look like to the cold eyes of the police?

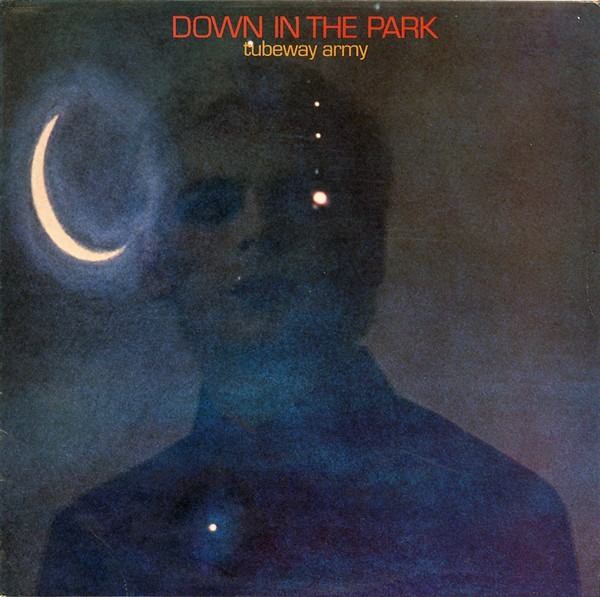

The police recur in the song 'Replicas' (we remember Thaemlitz's comment: 'behind their thin veil of sci-fi robotics, the images portrayed in the narratives themselves provide informative documentation of Great Britain's policing of social deviance and Gay male desire during the late 1970s and early 1980s ...') But before getting there we must pass through what may be Numan's masterpiece - 'Down in the park.' Here are the machmen again who 'meet the machines playing kill by numbers'. Sutton takes the idea of 'killing' very seriously and relates this back to 'The Machman' and the lines:

'I'd give it all up for you

I'd even be a number just for you

The strangest living boy

You could ever wish to see

'That's me'

He maintains on the basis of this that 'the strangest living boy' wants to play kill by numbers ie that he has a death wish. But throughout Numan's songs, death, killing, poison, disease like, as we have already seen, 'down', are indicators of sexual activity. An outstanding example being the spectacle of the twenty year old Gary Numan standing in front of thousands of young teenagers singing a song about masturbation. But it isn't a joke (not many jokes in Gary's lyrics). It isn't 'Something came over me' by Throbbing Gristle. It's called 'Every day I die' (which as it happens is a line in a poem written earlier by John Cooper Clarke). So I would suggest that the strangest living boy is longing for some very rough sex at the hands of the most brutal predators, the 'machines', who regard their lovers (if that's the right word) or victims (if that's the right word) as nothing more than numbers, totting up a score.

Unlike the boy in 'Down in the Park', who wants to escape the notice of the 'rape machine' in Zom Zom's, the café. Can anyone doubt that 'Down in the park' 'where the chant is death, death, death/'til the sun cries morning' is about group sex in a public park, perhaps, since we can assume it's London, Hampstead Heath? Any lingering doubt would surely be removed on seeing the video of the 1981 Wembley 'Farewell concert' when Numan slaps himself on the arse as he sings the line 'wouldn't believe the things they do.'

And let us note in passing that in Numan's sci fi fantasy the electric androids are all identical. But 'Down in the Park' finishes with the devastating line, 'Different faces but the words never change.' These are very human 'machmen'.

Though of course the whole point about the alien/android imagery is that in the actual sexual encounter, they are dehumanised:

'We are not lovers

We are not romantics

We are here to serve you.' (11) ('service' being another of Numan's indications of sexual activity as, very obviously, in 'Do you need the service?')

(11) Marilyn Manson's hysterical version projects the song into the realm of transcendent evil. He makes a real meal of these words. I don't believe in transcendent evil (I think the banality of evil is a much stronger concept) and I think Manson's version is a betrayal of the real strength of the song - its down to earth realism. Alas, Numan seems subsequently to have followed Manson's direction into the transcendental.

Which brings us to 'Replicas', which Sutton describes as 'one of the crowning glories of Numan's art.' He interprets it on two levels:

'When he sang the song in concert, Numan would raise and cock his hand downwards on the line, ‘And they seemed to think that I looked that way’, to indicate that the song was about a non-gay man being threatened by a gang of homophobes (with his dyed-hair and make-up Numan was often mistaken as being homosexual).'

Again I beg to differ. As I read it, the protagonist who

'Turned on the crowd

And I screamed "you and you -

it could have been you"'

has been 'had' by several men in the park. Having been 'down on the floor' (or in this case the grass) while the queers above him are out of order, he doesn't really know by which men out of the possibly quite large crowd who were present. His feelings are, as usual, confused: 'I suppose it was the shame.' Was it rape, or was it something he wanted? The police arrive (had he summoned them? Is that what is meant by the line 'I said it was me'?) But he doesn't bring charges. He just walks away.

According to Sutton's second level, however:

'It’s not a song about homophobia, it’s a song about a villain. The man at the centre of the drama isn’t being crowded by a baying mob because he is different or looks gay, the crowd are angry because he has just killed a whole load of people. He has slaughtered them because killing is his job ... In the second stanza, the protagonist is not talking about the nameless faces in the baying crowd, but the people he has just killed.'

There is nothing in the song to justify this interpretation, though the second stanza:

'You see we'd never met

And they didn't have names

There was nothing I could do'

would fit into it (in my reading it could be what he's telling the police). However, the camp gesture he has described earlier on the line 'they seemed to think/that I looked that way' appears in the 1980 live concert in Paris, accessible (at the time of writing) on Youtube and Numan's utterly menacing performance on that, especially when he plays his guitar solo, (12) could give some small credence to Sutton's otherwise very improbable thesis. I read it as simply a reflection of the depth of this supposedly unfeeling man's feeling. In some ways a lot of the power of what Numan has achieved can be interpreted as vengeance.

(12) As Sutton puts it: 'in comes Mr. Numan on his Gibson guitar to play the musical chorus and it is superb. After a finely strummed power chord has been struck and shook and starts to fade, he plays a swinging seven-note riff that is answered, after the sustained note on the seventh, by a three-note reply from the surrounding choir of synthesizers. It’s a gorgeous melody and a thrilling musical innovation ... and is very like something Monteverdi is writing in Heaven now that he’s been introduced to new sounds and new instruments and new ideas.' Difficult to disagree with any of that!

I have other quarrels with Sutton's interpretations but they open up new themes that might be better discussed in another article. The theme of this essay is, broadly, Numan's remarkable understanding of the rougher side of the gay (the word hardly seems appropriate) scene. It is a theme that tends to fade out of his subsequent work. I want to finish here but I'm aware that I've said very little about the music. What is truly remarkable is that this (one might think) rather grim theme - 'lies and shame', to quote Thaemlitz - is accompanied by such magnificent, triumphal sounding music. It's not by any stretch of the imagination happy music - it's not the Beach Boys - but it is music that asserts the importance and dignity of the apparently very undignified emotions of the lyrics. Undignified they may be but they are powerfully human. It is this tension between the radiance of the music and the despair of the lyrics that makes him so very unique and interesting.

I hope to be able to discuss later developments in a future article, or even articles (there's a lot more that needs to be said), but very briefly, so far as I'm concerned, the last Gary Numan album is the much maligned Machine and Soul. Thereafter, in his current phase (which has now lasted over twenty years) the ever more despairing lyrics ('I am dust', 'My name is ruin') have been accompanied by an appropriately dark and despairing music. A major theme is his hostility to religion and, more fundamentally, to God - Numan claims to be an atheist but it is difficult to see how one could feel such bitterness towards something, or someone, one believes doesn't exist.

Well, I've opened up another subject but I've also, I hope, indicated that a consideration of Gary Numan's lyrics is not as irrelevant as it might have seemed to my general theme of 'Art and religion.'

I started this article with Terre Thaemlitz and with the criticism made of him in the Gary Numan/Steve Malins book, Praying to the Aliens. It seems appropriate to finish with Thaemlitz's response:

'I am ending this text with an answer to the question of Numan's sexual identity, the disclosure of which simultaneously cemented and ignited every obsessively placed tinder in the theoretical framework I have built in my mind around Numan's work. It was nonchalantly disclosed by Numan's manager [Malins - PB] in response to a question which I had never asked, and considered rhetorical in any case - an irrelevant truth of essence conveyed via wires, dumbing my ears in telephone conversation [sic - PB] and made material amidst spools of faxes. As an answer which does more to question audience expectations than to clarify Numan's experiences, it remains a lie best left to Numan's own words:

'I don't believe you

You said "straight"

It's like giving up hope'

- She's Got Claws, Gary Numan (1981)'