BACK TO PICASSO

Rookmaaker gives around 1910 as the date of the crisis he attributes to Picasso, so he is talking about what is usually called 'analytical Cubism'. This is indeed the moment when the coherence of the subject that is being represented breaks down and one can see how Rookmaaker, attaching importance to the subject, would regard this as a catastrophic development. But this period in Picasso's development is also the period of his closest collaboration with Georges Braque, a period when even experts find it difficult to tell their work apart and there is much controversy as to which of the two was first with any of the particular innovations they were introducing. It may be easy to attribute absurdist intentions to Picasso, especially given the strain of mockery - and self mockery - that runs through his later work. It is more difficult to attribute it to Braque, careful and conscientious craftsman as he was throughout his life. All the evidence of the time points to two young men, each delighted with the exuberance of the other's imagination and each convinced they were doing something that had great possibilities for the future.

The real crisis in Picasso's development had already occurred, in the 'African' period, culminating with the Demoiselles d'Avignon. This was a violent rejection of the relatively facile (and eminently saleable) beauty and sentimentality of his earlier 'Blue' and 'Pink' periods. The African paintings were a reaction not just to his own earlier work but also to the currently fashionable 'Fauvism' of Matisse and Derain, which perpetuated a nineteenth century fantasy of a pre-Christian earthly paradise in which naked figures disport themselves freely in a beautiful landscape. Picasso, with his background in Spanish anarchism, wanted to show a much rougher reality. Describing a visit to the Musée d'Ethnographie in the Trocadero to André Malraux, he said:

'When I went to the old Trocadero, it was disgusting. The Flea Market. The smell. I was all alone. I wanted to get away. But I didn't leave. I stayed. I stayed. I understood that it was very important: something was happening to me, right? [...] The Negro pieces [...] were against everything - against unknown, threatening spirits. I always looked at fetishes. I understood; I too am against everything. I too believe that everything is unknown, that everything is an enemy! Everything! Not the details - women, children, babies, tobacco, playing - but the whole of it! [...] If we give spirits a form, we become independent. Spirits, the unconscious (people weren't talking about that very much), emotion - they're all the same thing. I understood why I was a painter. All alone in that dreadful museum, with masks, dolls made by the redskins, dusty manikins. Les Demoiselles d'Avignon must have come to me that very day, but not at all because of the forms; because it was my first exorcism painting - yes absolutely.' (22)

(22) André Malraux: La Tête d'obsidienne, Paris 1974, trans June and Jacques Guicharnaud, New York 1976, pp.10-11 quoted in Patricia Leighten: Re-ordering the Universe - Picasso and anarchism, 1897-1914, Princeton University Press, 1989, p.87.

Museum of Ethnography, Tocadero

Rookmaaker sees Picasso's 'Africanism' and animist religion as having in common a sense of identification with the forces of nature. It would be more accurate to see it as a perception of nature, including our own natural feelings as a menacing force. Which is how the German art historian, Wilhelm Worringer, understood non-naturalistic art in his great and highly influential study, first published in 1908, Abstraction and Empathy. It is the Fauvist nudes disporting themselves in a beautiful landscape who have a sense of 'empathy' with nature.

On this reading, the subsequent collaboration with Braque, including the 'analytical Cubist' phase was - at least in its intentions, whatever we may think of the eventual consequences - an unusually 'constructive' period in Picasso's development.

'Analytical Cubism' corresponds to the phase of Cubism Gleizes characterises as 'multiple perspective', the attempt to convey the real experience we have of the subject, incorporating both what we know about it and what we can see from different angles. But this ambition to present a fuller image of the subject is less obvious in the case of Picasso and Braque than it is in that of the Salon Cubists - especially Metzinger, even if Metzinger praised Picasso as the first person to attempt it. (23) Gleizes, when he first saw these paintings, referred to them as 'an impressionism of form which nonetheless they opposed to that of colour.' (24)

(23) 'Cézanne showed us how forms live in the reality of light; Picasso brings us a material account of their real life as it is lived in the mind; he lays the basis for a free, mobile perspective out of which the judicious mathematician Maurice Princet has deduced a whole geometry.' - Jean Metzinger: 'Note sur la peinture', Pan, no. 10, Oct-Nov 1910

(24) 'Metzinger must, with his intelligence more than with his painter's sensibility, have seen early on that painting was floundering about in researches that were undermining preconceived notions but which only touched the superstructure; and that the very precious insights of Picasso and Braque did not, in spite of everything, break free from an impressionism of form which which, nonetheless, they opposed to that of colour.' - Albert Gleizes: 'L'Art et ses représentats - Jean Metzinger', La Revue Indépendant, no.4, Sept, 1911

As the Impressionists and, more methodically, the Neo-Impressionists (Seurat and Signac) had broken down, or analysed, the colour of the subject in front of them in terms of the smallest element the painter could use - the brushstroke, or the point of colour - so Picasso and Braque were doing something similar with the formal elements of the painting, specifically the 'Cézannean' painting they had both been practising beforehand, when the subject had been divided up into small, clearly defined patches of colour which imposed on it a grid like construction (which recurs later in the century in the abstract paintings of Jean René Bazaine, Jean Le Moal, or Alfred Manessier - painters with a specifically religious or spiritual ambition). The raison d'être for Cézanne had been to intensify the colour relations but Picasso and Braque concentrated on the grid like structure as sufficient to itself at the expense both of the colour and the subject.

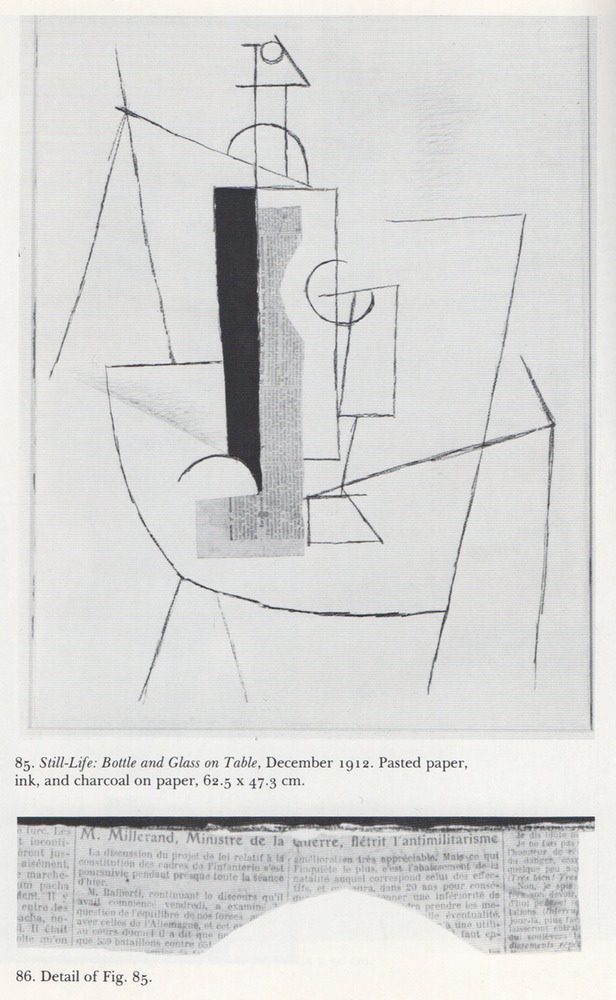

Georges Braque: Woman Reading, 1911

It is the next phase, commonly called 'synthetic Cubism', characterised by the papier collé, that Gary Lachman probably has in mind. Lachman is concentrating attention on the subject and it is the subject which, according to Gleizes, comes to the end of the road with Duchamp's Ready Mades. But we have seen how Picasso and Braque had concentrated on modest subjects whereas for Gleizes and his friends Cubism was a means by which ambitious, large scale statements about the world could be made. It might be said in parenthesis that scholars who have taken the trouble to read the newspaper articles neatly glued to the canvasses of the 'synthetic' period maintain that Picasso and Braque too were making large statements about the world, or at least about current politics - the 1912 Balkan wars for example. (25) But if the intention was to deliver a message about the Balkan wars, a message only received fifty years after the event, then it obviously failed. What was important and influential was, on the one hand, the treatment of the explicit subject ('mundane articles like cigarette packets' to quote Lachman; 'a very simple object, an inkstand, a box etc.' to quote Gleizes) which led the way to Duchamp; and on the other, the way in which the elements of the composition - simple plane shapes, much more clearly defined than in the 'analytical' phase - were organised which led the way to Gleizes (and, for that matter, to Mondrian, but that is another story. There is no principle in Mondrian's work that can go beyond what he himself achieved). Neither Picasso nor Braque in the event saw their adventure through. They both in their different ways fell back into a conventional subject-orientated idea of painting.

(25) See eg Leighten: Re-ordering the Universe, e.g. pp.121-42.

A page from Re-ordering the Universe showing Picasso: Bottle and Glass on a table with a close up of the pasted newspaper cutting: 'Mr Millerand, War Minister condemns antimilitarism'

Which is not to say that they were 'wrong'. Only that, following the line of thinking I want to develop in this article, they remained thoroughly ensconced in a post-Renaissance, 'Humanist' mode of thought.