CLASS POLITICS

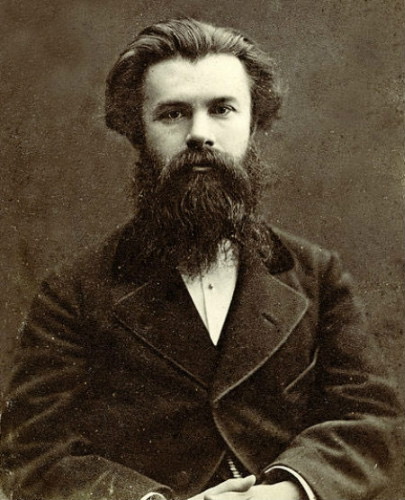

Mikhailo Drahomanov

So. The 'Ruthenians' in Austria and the 'Ukrainians' in Russia had it in common that they were both mainly peasant societies. They had lost their native aristocracy (it had effectively become Polish) and they hadn't been in a position to develop a bourgeoisie. There was a Polish artisan class in Galicia but otherwise the role of artisan, shopkeeper etc was mostly taken by Jews. Thus, although in Galicia a political consciousness (nationalist or socialist) could develop among the Poles on the basis of the aristocracy and artisan classes, for the Ruthenian/Ukrainians it was concentrated on small numbers of University students.

There was, however, a difference between the two peasantries. The Russian side included large numbers of peasants who had escaped from serfdom in Galicia, who had maintained their Orthodoxy in defiance of those of their priests who had converted to the Uniate/Greek Catholic Church, and who had joined the Cossacks - either the official Cossacks mostly west of the Dnieper, or the unofficial 'Zaporozhian' Cossacks mostly to the East - in conditions of almost perpetual warfare with the Tatars.

Despite their Orthodoxy, and despite the development of an impressive intellectual Orthodox centre in the Kiev-Moghila Academy, it is doubtful if these Eastern Ukrainians, soon to be incorporated into the Russian Empire, were well supplied with, or well organised by, an Orthodox priesthood (for what it's worth Gogol in Taras Bulba portrays their Orthodoxy as little more than a badge of identity). The distinct Ukrainian - intellectually European - Orthodoxy that developed in Kiev had, as we have seen, been tasked by Peter with the job of educating the wider Russian Church.

At the same time, under Peter (who took the territory East of the Dnieper) and Catherine (who had the territory West of the Dnieper as well as the territory to the South previously held by the Tatars), the Cossack tradition seems to have been successfully tamed, with the Cossack chiefs becoming landlords and the footsoldiers reduced to serfdom - hence the complaints of Shevchenko's poetry. And yet something of the independent Cossack tradition remained, ready to spring up again with the collapse of Tsarism in the twentieth century.

In Galicia, by contrast, the Greek Catholic Church became the organising centre for the Galician Ruthenian peasantry, and was encouraged in this by the Austrian government as a counterweight to the Poles. After the constitutional reform of 1861, when an elected 'diet was established in Galicia, the Ruthenians were mainly represented by Greek Catholic priests. When National Populist ideas began to spread among the Ruthenian student population they had no way of reaching the peasantry except through the church, which had its own programme for national education and improvement. As a result, populist literature aimed at the peasantry had a clerical character that was profoundly shocking to the Russian Ukrainian Socialist Mikhailo Drahomanov, when he arrived in Galicia in 1875.

The Ruthenian student movement in Galicia, such as it was, was divided between 'Russophiles' and 'National Populists', who could be called 'Ukrainophiles' though the Ruthenians weren't yet defining themselves as 'Ukrainians'. The National Populists had been inspired by Shevchenkos' poetry and by the Polish uprising that took place in 1863. Under the 1861 constitution, Galicia was treated as a unit, which meant that it was overwhelmingly Polish in character, despite the promise of a separate Ruthenian dominated Eastern Galicia which had been made in response to Ruthenian loyalty during the earlier Polish rising in 1848. It was the largest crownland in Austria, covering a quarter of the whole area, but very undeveloped in terms of industrial production. There was a population of about 6/1⁄2 million - 40% Poles, 40% Ruthenian, 10% Jews. The Ruthenians counted in Hegel's terminology (also used by Engels) as 'non-historical peoples' - peoples who had never formed a state and who lacked a nobility, unlike the 'historical' Russians, Germans, Poles, Magyars. By the early 1890s less than 20% of the students in the Universities of Lviv and Cracow were Ruthenian. In the Lviv Polytechnic, there were 83% Poles, 11% Jews and 6% Ruthenians. (1)

(1) The above account is mainly based on John-Paul Himka: Socialism in Galicia - the emergence of Polish Social Democracy and Ukrainian radicalism (1860-1890), Harvard Ukrainian Research Institute, 1983.

Nonetheless, the mere fact that, in marked contrast to Russia, there was an elected regional Parliament led Drahomanov to think Galicia had promise. Given the clerical orientation of the National Populists it was actually among the Russophile student group that he made most impact. The Russophile paper Druh (Friend) wasn't written in Russian but in the curious Ruthenian language of culture, 'Yazychie.' Drahomanov contributed articles in Russian which the 'Russophiles' had to translate, thus illustrating how far removed they were from Russia. Out of the Druh circle Drahomanov recruited two remarkable disciples - Mykhailo Pavlyk and Ivan Franko, both from poor peasant backgrounds, both studying at Lviv University but having great difficulty making ends meet. Drahomanov introduced them to European and Russian radical literature including Chernyshevsky, Lassalle, Mill, Dobroliubov. Pavlyk and Franko converted Druh from Yazychie to the peasant language, Ruthenian/Ukrainian, and in the Summer of 1876 the two Ruthenian student clubs united as Ukrainophile. Druh lost the financial support it had received from the Russophile establishment and was financed by Drahomanov. It took on a radical Socialist character. Through Pavlyk and Franko and under Drahomanov's influence, Galicia became an important conduit for the smuggling of revolutionary literature, mainly from Switzerland, to Russia.

Drahomanov was a leading member of the 'Kyiv Hromada', described by the Encyclopedia of Ukraine as 'the most important catalyst of the Ukrainian national revival of the second half of the nineteenth century.' Its earliest activities had been devoted to producing educational material for Sunday Schools using the peasants' own language - a similar project to the one undertaken by the Greek Catholic Church in Galicia. But that came to an abrupt end in 1863 with the issuing of the 'Valuev Circular.'

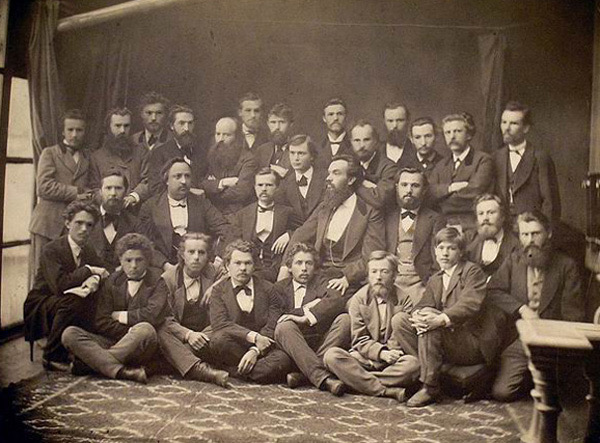

The Kyiv Hromada, end of the nineteenth century

Petr Valuev was Russian Minister of the Interior under Alexander II, the 'Tsar-Liberator', responsible in 1860 for the emancipation of the serfs. This, however, had been followed in 1863 by the Polish insurrection. There was no particular suggestion of a Russian Ukrainian sympathy for the Poles or of any great sympathy for Ukrainian separatism, despite the popularity of Shevchenko. But the Polish rising illustrated the dangers of separate national identities. Already in July 1862, Valuev had written to Alexander Golovnin, the Minister for Public Education calling on him to ban Yiddish publications and the use of Yiddish in education:

''[the ban] will prevent the further literary development of the slang [zhargon] and thus remove the possibility of it ever becoming the means for expressing those concepts that the Jews will, with the expansion of education among them, adopt from Russian and German books. [The ban] will thus promote a gradual replacement of the slang by Russian …' (2)

(2) Johannes Remy: 'The Valuev Circular and Censorship of Ukrainian Publications in the Russian Empire (1863-1876): Intention and Practice', Canadian Slavonic Papers / Revue Canadienne des Slavistes, March-June 2007, Vol. 49, No. 1/2, p.91.

Golovnin opposed this ban but by 1863 Valuev's ministry had taken over the administration of censorship from the Education Ministry and he was in a position to move against Ukrainian. As with Yiddish, Ukrainian was regarded as not a real language - 'nothing but Russian corrupted by the Polish influence.' The aim was 'to license for publication only such books in this language that belong to the realm of fine literature; at the same time, the authorisation of books in Little Russian with either spiritual content or intended generally for primary mass reading should be ceased' (Remy, p.92). So it was not a total ban. The upper classes could read 'fine literature' in the peasant language but it couldn't be used as a medium for the education or spiritual edification of the peasants themselves. Thus an obstacle was placed between the Ukrainian cultured class and the peasantry which contrasts with the role of the Greek Catholic priesthood in Galicia. The Valuev Circular, which was simply an administrative measure, was strengthened in 1876 by the 'Ems Decree' which widened the range of material that was banned (anything of an informative, non-literary nature) and gave it legislative force. The ban on the popular or educational use of the Ukrainian language continued until 1905.

Although the Kyiv Hromada was formally banned early in 1863 it continued in existence, concentrating on cultural activities and historical research. Drahomanov joined in 1869, and in 1873 he was instrumental in establishing the 'Southwestern Branch of the Imperial Russian Geographical Society.' He also edited a daily newspaper, the Kievan Telegraph, a Ukrainophile rival to the Russian Conservative paper, Kievlanin. With his colleague, Volodomyr Antonovych, he published a two volume 'Historical Songs of the Little Russian People', following it in 1876 with 'Little Russian Folk Legends and Tales.' But 1876 and the Ems Decree saw the suppression of the Kievan Telegraph and of the Southwestern Branch of the Geographical Society and Drahomanov dismissed from his post in Kiev University. When he went West (in his dealings with Galicia he was mainly based in Geneva) it was as a representative of the Kyiv Hromada. He established a Ukrainian language press and published a journal, Hromada (5 vols, 1878-82), 'the first modern Ukrainian political journal', according to the Encyclopedia. He was also involved with the Russian Liberal emigration, editing their journal, Vol'noe Slovo. But the Kyiv Hromada itself, concentrating on cultural studies, broke with him in 1886, not wanting to be associated with his politics.

Which were still more Socialist than Ukrainian separatist - an anarchist Socialism envisaging a federation of free peoples rather than a centralised planned economy (he published collections of letters by Turgenev and Bakunin addressed to Herzen). His disciples Pavlyk and Franko were imprisoned, albeit briefly (Austria being at the time vastly more indulgent in this respect than Russia) for their activities and in particular Franko's promising career - he had published a well received collection of stories centred on the oil extracting town of Boryslav - was wrecked. Franko was a social realist of the sort Belinskii would have appreciated were it not that he wrote in Ukrainian.

Their trials made a huge impact without however yet generating a substantial political movement. The problem in Galicia was the lack of a substantial social base for a political movement. Pavlyk and Franko were both heavily involved in the militant movement that was developing among the artisans of Lviv but these were almost entirely Polish. Access to the Ruthenian peasantry still had to pass through the Greek Catholic Church.

But that was changing, largely through the Church's own efforts. As an alternative to the tavern the Church was establishing Reading Clubs, which soon spread like wildfire. In Himka's account (p.122):

'There were only a handful of these clubs in the 1870s, but hundreds in the 1870s and thousands by the turn of the century. In the reading club, the minority of literate peasants would read aloud to their unlettered neighbours. They read popular newspapers and booklets filled with information on saints, agricultural technique and, especially, politics. The peasant began to be aware of his or her national identity so that in a very real sense the growth of the network of reading clubs was synonymous with the growth of the nation.'

Nothing of the sort, of course, was happening in Russia. There was an impressive intellectual élite researching history and folklore but prevented by government policy from making much contact with the folk; there was a conspiratorial elite which, after the failed attempt to 'go to the people', was now engaged in terrorist activity on the people's behalf (but so far as I can see this didn't yet engage any specifically Ukrainian cause); and there was the folk themselves whose frustrations towards the end of the century were taking the form of spontaneous anti-Jewish pogroms. It could be argued that this was at least partly a consequence of the government's policy of preventing popular education in the people's own language, cutting off the connections that could have been formed between the University educated class and the peasantry.

The period covered by Himka's book on 'Socialism in Galicia' ends in 1890, the year which saw the formation of the first Ukrainian political party. This was the 'Ruthenian-Ukrainian Radical Party', established in Lviv in October, inspired by the ideas of Drahomanov, Pavlyk and Franko, though Drahomanov himself thought it was premature and never formally joined. It was at that congress that the question of an independent Ukrainian national state was first raised. Viacheslav Budzynovs'kyi (1868-1935) proposed as a maximum demand the unification of all the Ukrainian territories in an independent state and as a minimum demand, the division of Galicia into two parts, one Polish and one Ukrainian. (3) Prior to this the most radical Ukrainian demand had been for autonomy within a Pan-Slavic state. It was because documents arguing for this were found in their possession that, in Russian Ukraine, the members of the Society of SS Cyril and Methodius had been sent into exile in the 1840s. Drahomanov also advocated Ukrainian autonomy within a wider federation and this was generally the position favoured by the Radical Party. Budzunovs'kyi got no support for his motion but he did get some support from a group of his fellow students in Vienna who produced an open letter calling for the creation of an independent Ukrainian state. Franko and Pavlyk replied, arguing that the proposal would only serve 'the interests of those strata who would be the first to benefit from the eventual establishment of an independent Ruthenian state, whereas the fate of the working people in this independent state could even deteriorate.'

(3) John-Paul Himka: 'Young radicals and independent statehood: the idea of a Ukrainian nation state, 1890-95', Slavic Review, Vol. 41, No.2, Summer 1982, pp.220-1.

1895, however, saw the publication of what is widely regarded as the first serious argument for an independent Ukraine - Ukrainia irredenta, by another young radical (he had supported Budzunovs'kyi in 1890 but, as a gymnasium student, didn't have the right to vote), Iuliian Bachyns'kyi (1870-??, the question marks meaning of course that he ended up in the Soviet Union). This argued for 'a free, great, politically independent Ukraine, politically independent from the San to the Caucasus.' The San is a tributary of the Vistula on the Polish side of the current Polish-Ukrainian border. Things were moving quickly. In December 1895 the Radical Party adopted a resolution similar to the one put forward by Budzunovs'kyi in 1890 and 1899 saw the emergence of two new Ukrainian parties with a Nationalist programme - the National Democratic Party and the Ruthenian-Ukrainian Social Democratic Party (Bachyns'kyi was a founder member). In 1900 a series of articles calling for independence was published in the main Ukrainian language newspaper, Dilo, Franko published a pamphlet - Beyond the bounds of the possible - in support of it and a mass student rally was held in Lviv on July 14.

Himka interprets this as a development in Socialist thinking towards Marxism. Drahomanov as a follower of Bakunin, was suspicious of any centralised state. By 1900 the argument had developed that Socialism could only develop on the basis of industrial capitalism and the Ukrainians could never develop industrial capitalism so long as they were part of a larger state having to compete with Bohemia or Vienna. Pavlyk and Franko had criticised Budzunovs'kyi and Bachyns'kyi not for their nationalism but for Marxism. Nonetheless, Himka says (Young Radicals, p.230), 'Drahomanov, in a sense, broke the ground for the advocacy of independence.' In the mid 1870s, he says (p.233), there was no talk of independence: 'A handful of intellectuals in the cities was involved in a cultural nationalism that had little connection with the overwhelming majority of the nation, the peasantry.' It was the church that was providing the connection between its own intelligentsia and the peasantry through the establishment of the reading room as an alternative to the tavern. But Drahomanov formed a radical intelligentsia able to take advantage of the reading rooms for the development of secular politics. In summary Himka says (p.235):

'Ukrainian statehood was first championed in Galicia, where the constitution and the existence of a nationally conscious clergy permitted the sort of development described above [the formation of the Reading Room movement, 'Prosvita' - PB]. Where this development was lacking, as in Russian-ruled Ukraine, the great majority of the Ukrainian intelligentsia could not see beyond federalism, until war and revolution opened their eyes.'