THE PRINCIPLE OF INSULAR ART - RHYTHM

The main writings in defence of images were not made available in the West but we can perhaps imagine that if the insular artists had encountered them they would have found them - particularly the passages I have just read from Saint Theodore - quite incomprehensible. Simply because they did not have the idea of 'likeness'. It would never have occurred to them that their job was to copy the external appearances of nature. Had such an idea occurred to them I think they would have thought it an impossible task because in order to capture the external appearances of the natural world in sculpture or in painting you would have to rob it of its most salient characteristic, which is movement and change. Reading Theodore the Studite I myself found it difficult to resist the rather malicious thought that what he was writing about was not painting at all but rather photography. Christ could not have been human had it been impossible - given the right equipment of course - to take a photograph of Him.

We do not have (so far as I know) a treatise which explains in words what the insular artists were trying to do but it is quite clear from the art itself that they were working to a clearly understood philosophical and theological end. They were monks, so we can be sure that this was part of the discipline they believed would be helpful in the passage through time to Eternal Life. Both for the person working on the manuscript and for the person looking at it, this was an art of contemplation. Living in or coming from Ireland we may risk being overfamiliar with this work and losing the sense of just how remarkable it is. I hope you will forgive this effort to understand what we may think we already know.

It is in the first instance a 'decorative' art. We have the bad habit, when we use the word 'decorative' of prefacing it with the word 'merely'. This fear of - or contempt for - the 'merely decorative' is not just a problem in our understanding of a large part of the history of the visual arts, it is also, I would argue, one of the reasons for the failure of twentieth century 'abstract' or non-representational art. We are not satisfied with decoration as the satisfaction of a simple human need - we feel the work has to 'represent' or 'express' something other than itself.

But the human need for decoration is profound and goes very centrally to our conception of what human nature is. The task is to turn a given space into a source of delight. To do so it obviously has to correspond to our human nature. A frivolous decoration implies a frivolous idea of human nature. A profound idea of human nature - for example the idea that the individual human soul is immortal and our passing life in time and space opens out into Eternity - will give rise to a profound decoration. And this is what we have to a truly outstanding degree in insular art.

Perhaps the most important characteristic of this art is the understanding that human nature functions in both space and time. The decoration is in the first instance, as always, a structuring of space and this is largely a matter of dividing the space through the use of vertical and horizontal straight lines that stand in a clear, visually comprehensible relationship to the overall frame, usually clearly asserted.

[Fig 5] Book of Kells (c8th/9th century), TCD Library Ms 58, folio 203r, opening page of Luke Ch 4.

This is essentially an art of proportion and measurement, but it is still not an art of time. Time is built into the structure of the painting through the movement of the eye which has to be guided in opposition to our normal habit of jumping from one thing to another. That guided movement has to be kept within the bounds of the overall area to be decorated, within the structure given by the proportional divisions of the space. If it goes outside those limits the movement will stop. If the movement is not to stop it has to be essentially circular, it has to return on itself. The principle is expressed most clearly by a circle inscribed in a rectangle. We may be reminded of the circle inscribed in the chair of the portrait of Saint Mark in the Book of Dimma.

[Fig 6] Detail from illustration 4.

A circle presented baldly, however, can be seized by the eye all at once and therefore experienced as a static figure. In order for the circle to be experienced as a circular movement functioning in time it has to be slowed down and this is the function of the complications, the wheels within wheels:

[Fig 7] Detail from theBook of Durrow (c8th century), TCD Library Ms 57 folio 192v.

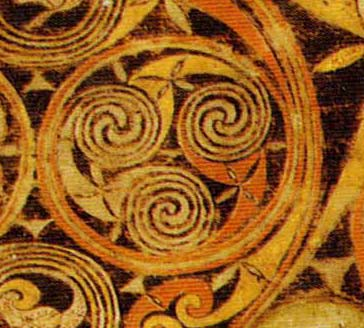

the spirals:

[Fig 8] Detail from Book of Durrow, folio 3v.

the stretching out of the circular principles into elongated arabesques which still turn back on themselves:

[Fig 9] Detail from Book of Lindisfarne, British Library, Cotton MS, Nero, D.IV, folio 139r (opening page of Gospel of St Luke - the drawing is taken from the tail of the Q in Quoniam).

and the passing of the movement from one centre to another:

[Fig 10] Detail from the Book of Durrow as in illustration 8.

The appearance of representational shapes - animal or human heads for example - do not alter the principle I have been trying to outline but they do suggest an attitude to the appearances of the natural world which is radically different from that of classical art. This is not a scorn for the appearances of the natural world but it is a recognition that those appearances are in constant flux. They are subordinate to, indeed a product of, the overall movement. the so-called 'primitive' appearance of the faces, even on pages in which the figurative image is central, simply reflects the scribe's lack of interest in anything that does not contribute to the dynamism of the decoration. A parallel may be drawn with the many sketches I have seen of Romanesque art in which the interest of the classically trained copyist has been concentrated on the figurative aspect and especially the face. The rhythmic movement which is to be found in the folds of the garments and which is the centre of my own interest and, I believe, that of the original artist, has been rendered in a very casual, slapdash manner.

I said at the beginning of this discussion of the insular manuscripts that there was no treatise to explain clearly what the monks who created them thought they were doing. There are, however, indications that the action of time would have been very much on their minds. Leaving aside the elementary religious emphasis on the transitory nature of the world, this is the period when Augustine of Hippo was coming into his own as the Latin Father par excellence. The eleventh book of Augustine's Confessions contains a reflection on time which, Augustine says, 'is coming out of what does not yet exist, passing through what has no duration, and moving into what no longer exists.' Boethius's treatise On Music is largely concerned with rhythm, which is to say the organisation of time. And the great work of John Scotus Eriugena, the ninth century De Divisione Naturae is also largely a reflection on time, for example his discussion of how time destroys the categories by which Aristotle tries to define reality. [7] Classical art could be described as Aristotleian, respecting the categories. If we imagine what an art based on the arguments of Scotus Eriugena would look like, we may arrive at something resembling insular art.

[7] Johannis Scotti Eriugenae: Periphyseon (De Diuisione Naturae) Liber primus, edited and translated by I. P. Sheldon Williams (with Luwig Bieler), Institute for Advanced Studies, Dublin, 1968. Discussion of the categories pp.85 et seq.